Top down Culture and Fire

Jan 1, 2015

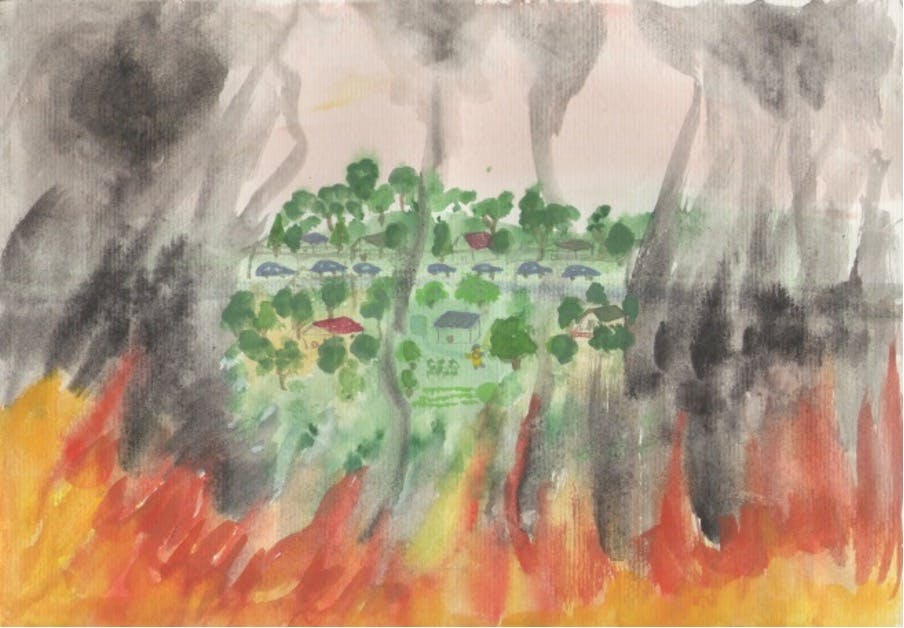

It is tempting for us to think of climate change as the main culprit that caused the October Blue Mountains fires in 2013. The climate change protests that followed were directed to government. Yet the best way to address climate change or home loss destruction due to fires is to admit to our own responsibility and power. There are low impact measures we can take as homeowners to reduce the risk of home destruction due to fire. All though it may feel right to lobby and attend protests, it is naive and illusory to expect government to make any immediate significant changes regarding climate change, or the vulnerability of Blue Mountains communities to fire.

In taking action to address climate change and our vulnerability to fire as individuals we will encounter top down challenges and our own cultural impediments. Becoming aware of the top down challenges and our own cultural impediments is essential to our taking action to prevent more home loss effectively.

As I exposed in Reduce the Fuel Reduce the Risk, the two actions that need to happen to decrease the risk of home loss due to fire are.

1. Removal of fire promoting trees close to power lines;

2. Removal of fire promoting trees away from houses;

And these issues will be addressed separately here:

1. Removal of fire promoting trees close to power lines;

The top down challenge

Typically power lines run parallel to the front of our properties on the street. The power lines are on Council land. However according to Council, as the power line companies have the liability for damage from their power lines they also have the responsibility of assessing risk and instructing removal and pruning according to NSW legislation.

Power lines companies have the power, not you.

The power distribution company around Springwood, Endeavour Energy, has the responsibility to clear branches away from power lines. But NSW legislation only permits them to clear branches a few metres from power lines. Even if we believe trees are too close to power lines, we are not legally allowed to remove the trees. Nor do the power companies have the right to clear beyond those few metres.

This 25m tall radiata pine standing beside and above these power lines is a typical example of how close large trees are next to power lines in the Blue Mountains. It stands 15m from my house on the neighbour’s side of the fence. An Endeavour Energy consultant informed me that power would have to be turned off in order to prune around this tree. This is a costly exercise involving the disconnection of electricity in the area, and therefore it would be very unlikely that the tree would be pruned. Fortunately for me my new neighbour has taken on the job of removing the tree at his own expense and with no collaboration from Endeavour Energy, however there are many examples of this kind in most streets and roads in the area and not everyone can afford such expense.

RFS risk assessment tree’s next to power lines

The RFS informs me that the pine tree next to power lines is not a danger. However bushfire science as outlined in my first article of this series, “Reduce the Fuel Reduce the Risk” recommends that power lines are kept clear of trees.

Most “nature strips ” in the area have a combination of trees lined up next to power lines, mostly they are fire promoting natives and pine trees. However without a positive risk assessment from RFS of such trees, Council will not allow their removal.

Cultural impediments to taking action regarding Power lines proximity to trees

My conversation with the Endeavour Energy consultant, during her tree inspection at my garden, veered off to personal opinion where we introduced ourselves and spoke informally. She expressed her concern about what will happen to the Blue Mountains if new NSW legislation allowing home owners to remove trees 10 metres away from their home takes effect. Alarmed, she told me something I have many times heard here in the Blue Mountains, of her worry of trees being removed from streets and backyards. There is a prevailing fear that removing native trees from the streets will drastically change the look of the Blue Mountains; the talk is of deforestation, ugliness and environmental impact.

An effective way to reduce the risk of home loss due to fire would be to replace the fire promoting trees with fire retardant species. There are many fire suppressing trees and plants suitable to Blue Mountains climates, and many of these are also attractive useful and edible species. We can love our native trees but acknowledge that most of the indigenous species around here are fire promoting and compete with the fire retardant species, and so should be kept away from our streets, backyards, and power lines.

In brief, the fear of deforestation where we live on the ridge tops of the Blue Mountains is short sighted. Should we stop focusing on what we see from our home and car windows and take a look at the bigger picture? google maps is a useful tool.

As exposed in “Reduce the Fuel Reduce the Risk”, never have power lines been so close to fire promoting trees as they are now. The photo below shows is an example of the suburban landscape in the 60s in Australia where power lines were still clear from trees.

Mount Pritchard, 1964. Picture: Justice and Police Museum, Historic Houses Trust of NSW Source: Supplied

Given that here in the Blue Mountains fire promoting trees are now fully-grown and next to power lines the risk is greater and so should be our preventative measures to save our homes. Consider that the loss and deforestation in our streets and homes caused by fire outweighs by far the cost of replacing some trees on these ridge tops for improved fire safety. To do this requires us to re-consider our landscape values and aesthetics. There are many suitable fire deterrent species for a suburban landscape and removing fire promoting trees does not mean that we need to revert a suburban landscape as bare and sterile as the one shown in the image above.

The Victorian Environment Protection Authority calculated the ecological footprint of building a new home to be 27 global hectares, of which 43% is forest area required to supply timber. See more here, on page 15.

Also: Australians currently send approximately one tonne of construction and demolition waste per person per year to landfill. This can make up to 40% of landfill. Materials include metals, concrete and bricks, glass, fittings and fixtures from demolished or refurbished buildings, wood and wall panelling. See ABS page.

Let’s not fail to see the forest for the trees. Our Blue Mountains residential landscape, where we keep fire promoting trees around our houses, is causing unnecessary forest destruction elsewhere to replace our homes when they are burnt.

2. Removal of fire promoting trees away from houses;

Top down challenges

In the Blue Mountains, according to the Tree Preservation Order “A person shall not, except with consent of the Council, cut down, top, lop remove, injure or wilfully destroy any tree the subject of this Order, which has a height of more than 4 metres, where any one or more trunks have a diameter of 0.35m (at a height of 1 metre above the ground), or has a foliage crown spread of more than 4 metres.”

This order certainly leaves very little margin to what homeowners can do to make a fire protective garden.

NSW legislation has been announced that is to allow home owners to remove trees that are 10 metres away from the house without permission. This is some improvement, but is still inadequate given the extreme landscape factors of the Blue Mountains as exposed in Reduce the Fuel Reduce the Risk.

Cultural impediments to taking action to removing native trees around home

Recent trends have increased the fire risk around our homes. Not so long ago the typical Australian backyard was a bare square of lawn, with not much in it other than a hills hoist, perhaps some deciduous trees away from the house, and a vegetable garden. Most gardens in the 1950’s did not include native species, which was probably a matter of taste and culture and fashion at the time.

With lifestyle changes, which include commuting and less time at home, growing food practices almost ceased and gardens became ornamental. However it was soon obvious that ornamental gardens had high water requirements.

A love for the Australian flora emerged with a trend to plant natives instead of introduced species in the 70s. This trend has transformed the gardens of Australian homes, and increased their fire risk significantly.

Talking to long time residents of my street here in Springwood I feel that the cleared properties that were once the norm made their houses defendable. These days my neighbour Ralph refuses to leave when fire approaches. He told me the story of his elderly neighbour Flora, who has lived through many fires here in Springwood. “We could see the fire, it was almost in our back yards, so I knocked on Flora’s door and said ‘Flora! What are you doing? Lets go!’ And she said, ‘Oh no, I’m watching the cricket, don’t worry about the fire, it will pass.’

And this was meant literally, as the fires can pass when properties are landscaped for fire prevention. Flora had a typical 1950’s garden and was prepared with water buckets to put out the spot fires.

So what was happening before the 1950’s? Why was that generation more fire savvy than the present.

The people who settled the Blue Mountains were not foolhardy and ignorant of fire risk or the flammability of the vegetation. They could hardly be, as early explorers and the first settlers describe Aboriginal people as constantly lighting fires. Before settlement even sailing captains wrote of the many fires they could see on-shore. Early settlers knew very well how the vegetation could burn.

Historical records (for example as set out by Bill Gammage in The Biggest Estate on Earth, How Aboriginal People Made Australia) describe how Aboriginal people, through careful and highly skilled use of fire, managed the landscape to maintain pasture, to assist hunting, and also for safety from catastrophic fire. It is likely that the “very pretty wooded plain” that Governor Macquarie described at Springwood in 1815, and which became a favoured camp site for European travellers, was what we might now describe as open wooded grassland. If it had been forest with bushy under-story (usually described by settlers as ‘scrub’) it is unlikely that Englishman Macquarie would have found it so pretty and described it the way he did. The recurring description across Australia of the Aboriginal managed landscape, used by the English explorers and first settlers, was ‘like a Gentleman’s park’ (Gammage).

Aboriginal management mostly ended with settlement, but was followed by timber getting, and clearing. Photographs of early Blue Mountains settlements show towns set in heavily cleared landscapes. Today we prefer more shade and rustic beauty. Those heavily cleared landscapes look harsh and barren to our modern taste, but we can understand that they were functional for fire safety. In more recent times we have embraced Australian native plants, and overlooked the very high flammability of some of these species.

Conclusion

It was perhaps the proximity to the history of early settlers that gave the people of the 1950’s the fire awareness to prepare for fire. But now faced with:

The predominantly flammable street and garden landscapes and heavy fuel loads;

More extreme weather conditions;

An extensive power line presence:

Scientific evidence based on history and research;

We need to give greater attention to our flammable landscapes around our homes and take basic fire destruction prevention measures such as clearing fire promoting trees from around our homes and power lines.

People who love the environment of the Blue Mountains with it’s trees fear that removing flammable vegetation from around houses and power lines will change the look of the area. However from an environmental point of view, if we don’t take serious measures such as clearing trees away from power lines and our homes, we risk being responsible for far greater deforestation.

A direct impact of construction activity on the environment is its use of resources which come from forests or land elsewhere. We will be partly responsible for the impact and deforestation if we have to rebuild due to fire destruction.

Knowing that building is a high impact activity and knowing the trauma that loss has caused, we need to take a proactive approach to fire prevention. And put into perspective the loss of a few trees around our homes. We need a collective effort in addressing climate change and our vulnerability to fire. We can do this as a community by taking environmentally responsible action regardless of what the government is doing about climate change or anything else.

A bottom up, safe, and resilient community is not an unattainable goal once we choose to face the challenges of top down culture. This means appealing to council when our applications to seek permission to remove trees are denied.